Hi friends,

I wrote another long letter today because I’m going to try not to do a lot of covid thinking over the holiday weekend. (If you’re new here, you might want to read the intro post. If you were on my original friends-of-friends email list, now you’re on this one, it’s like magic.)

Omicron is racking up record case numbers in countries all over the world right now—even without sufficient test capacity to meet demand in many areas, even with loads of people using unreported tests, and even before omicron really takes off in many areas. With a new school term a couple of days away, I want to quickly look at disease severity and then talk about pediatrics, but first, I am obligated to wave a flag that says:

TEST POSITIVITY IS NOT A GREAT METRIC

Test positivity often doesn’t mean what we want it to mean AND is weird in the US for a billion reasons relating to our data systems. But it’s extra weird right now because case and test backlogs resolve at different speeds, which borks positivity calculations. I recommend getting your positivity numbers only from your local health authority—not from national orgs that don’t adjust for local data problems—and please take them with extra chunks of salt for another 10-14 days.

Real-world disease severity still looks lower for everyone

In extremely good news, the early hopes about Omicron’s reduced severity compared to Delta seem to be holding up. The UK, which is a couple of weeks ahead of the US in the Omicron wave, is posting covid case numbers twice as high as its previous record. But although covid hospitalizations, are definitely up, they’re not even approaching last winter’s levels despite the huge case spike.

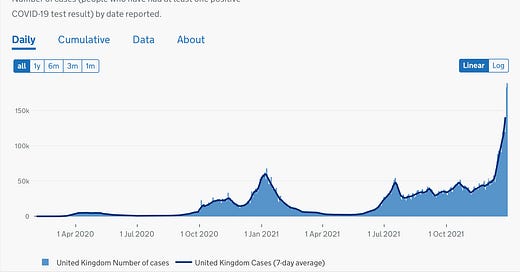

I try not to be super charty, but visuals are helpful for this one. Here’s the UK case curve, with cases by date reported—you can see Omicron spiking way up on top of the country’s relatively high Delta plateau and then blowing away last winter’s case numbers.

And here’s the “patients in hospital” chart from the same source, which shows that despite the surging cases, hospitalizations remain well under a third of last winter’s hospitalization peak. (In even better news, the number of covid patients requiring ventilation in UK hospitals is essentially flat.)

That doesn’t mean we’re in the clear about everything—a small percentage of a huge number will still be lot of sick people. The UK is setting up field hospitals, and staff shortages are reducing hospital capacity—in London, hospitals are seeing a 30% increase in staff absences as Omicron burns through healthcare workers, and the NHS is planning for a worst-case scenario in which 40% of its staff is out sick with covid at the same time. But it does look like we can start to trust the early indications that Omicron is not going to produce nearly as many severe cases, especially in vaccinated people. More on that next week.

Back to school during Omicron

Until now, schools have largely not been apocalyptic outbreak-seeding hotbeds of infection. There are plenty of outbreaks and in-person school bumps case rates a bit over remote instruction, but not a ton, and it seems like masking reduces that. But now we have Omicron crashing through just as schools reopen and everyone comes back from a holiday break, and our data about schools is based on previous, less transmissible versions of the virus.

So where are we at with Omicron and kids?

Despite some big claims on social media, we still have no reason to believe that Omicron is intrinsically harder on children than Delta has been. What we do have is a whole lot of covid infections, which lead to scary headlines featuring percentage increases. In NYC, for example, pediatric covid hospitalizations went up 400% from the week ending December 11 to the week ending December 23, which sounds pretty alarming—but in absolute numbers, that’s an increase from 22 children to 109 in a city of nearly nine million people.

Of course, for every family represented in those statistics, it doesn’t matter whether Omicron is less severe or just extremely widespread—it only matters that their kid is seriously ill. I feel that in my bones. But I think it’s useful to try to keep a clear head about the absolute risk of severe disease, which remains low for children.

We’re also really starting to see the difference between age brackets with access to vaccines. For the week ending 12/26 in NYC, there were 21 covid hospitalizations per 100k kids aged 0-4, none of whom have access to vaccines. By contrast, there were only 9 hospitalizations per 100k kids aged 5-12 for the same time period, and—according to the local health authorities—zero hospitalizations in the 5-12 age bracket among fully vaccinated kids. Granted, this only covers clinically severe illness, not the risk of long covid, but it’s a start.

It’s also worth remembering that our unvaccinated babies remain at a much, much lower risk than our now highly vaccinated population of elders. People over 75 have much lower case rates than any other age bracket in NYC right now—less than half that of the kids aged 0-4—but even with widespread vaccination, and even with those low case rates, we’re seeing 80 covid hospitalizations per 100k people over 75. Vaccines are amazing, but our elders and little kids still need protective measures, and so do the many thousands of people with compromised immune systems and other major risk factors, including refusing vaccines. Promising therapeutics are only months away from wide-ish distribution here in the US, but we’re not out of the woods yet.

So let’s say you have someone in your family who can’t be vaccinated, or who is high risk for other reasons—young children, immunocompromised people, the whole range. And you want to ideally protect that person from infection during a big Omicron surge. How can you accomplish that without pulling up the drawbridge and isolating everyone again?

First, nothing is certain, low risk isn’t no risk, etc. But there are things we can do to help reduce the likelihood of the outcomes we don’t want.

Household transmission isn’t a given

The “secondary household attack rate” for covid—a measure of how many people in a household end up getting covid after one person gets sick—isn’t anywhere near 100%, even with Omicron. In a recent Danish study, it averaged around 30% for Omicron across households with various vaccination situations. (This study’s a preprint, but it correlates pretty well with other studies on household attack rates and relies on official health data.) There are a bunch of potentially confounding factors—especially that lots of household members never get tested—so the main thing I think is interesting here isn’t the exact percentage of people who get sick, but the fact that it’s not everyone.

This is why I think frequent testing matters so much, especially if you have someone vulnerable in your home or immediate circle. If you can find an infection early, that person can isolate and seriously reduce the chances of everyone in the home getting covid. At-home tests are scarce, but not totally unfindable in many areas with serious outbreaks, and the supply will eventually loosen back up. If you can get them and use them routinely—probably focusing on the person or people with the most exposure unless someone shows symptoms—you can reduce your overall household risk.

Reducing everyone’s attack surface protects the people who need it most

It looks like most Omicron infections won’t be life-changingly bad, which is incredibly great and a huge relief. At the same time, every new infection is a chance for the virus to reach more people who will be vulnerable to serious illness. If you’re trying to protect people in your home and community, this is a good time to go all-in on the measures that reduce transmission for everyone without requiring a monastic life: high-filtration masks (many of which are honestly more comfortable than most cloth masks anyway and work much better), lots of fresh air and air cleaners, shots for everyone who can get a shot.

If you’re sending a kid back to school during a big local outbreak, that might mean upgrading their masks and checking to see if their classrooms have or will accept HEPA air filters and pressing administrators to keep windows cracked—which might in turn mean that some kids, classrooms, and schools will need donations of extra warm clothing. (And while you’re at it, US friends, if you happen to be have the resources to pick up extra air purifiers, there are almost certainly shelters, public school classrooms, and other public service providers in your area who could use them—just call ahead before you buy to see who needs what.)

None of these actions at the individual and small-group level are as effective as a whole-of-society response, but they’re not nothing, either, and I think that’s worth saying.

Love to all of you.

Erin