Welcome to the first Calm Covid update of 2023—a year that I hope will bring better health and more safety, love, and happiness to all of us. One of the big things I want to work on this year is a broader defense (maybe more of an offense) against the forces of true alarmism on one end of the continuum, and false reassurance on the other. I’m not sure what form that will take, but it will likely be closely connected to the level-headed comms work we tried to do at the Covid Tracking Project.

For today, though, a few things about where we’re at and what’s happening to us. A digression first, then a speedrun through some data.

[If you’re new here, hello! Please check out the intro to this accidental newsletter for more context.]

The (exhausted, coughing) elephant in the room

After months of seeing nearly all my friends with kids go through round after round of unexpectedly severe colds, flu, and RSV, I’m finding it hard not to think about the knock-on effects of covid: autoimmunity in long covid, of course, but also the possibility of increased susceptibility to infections after covid—a subject so touchy it’s nearly radioactive.

If that makes you want to click away, I get it! Bear with me for just a few more lines, I promise not to jump off the cliff of wild speculation.

In terms of the body of evidence on long-term effects, covid is still a baby pandemic, and although there’s good reason to believe that lots of odd things are happening in our immune systems, both during and for months after covid infections, it’s too early to know for sure how this will play out in the real world. (I won’t go into “immunity debt” here except to say that even in areas where few people masked up, flu and RSV have been making a ton of kids really ill, that immunity is complicated, and that simple explanations are likely to be incomplete at best.)

If you’re online a lot, you may know that quite a few sensationalists—many without specialist medical backgrounds—have taken advantage of this uncertainty to make super-firm, alarmist statements about what covid does to our immune systems and how scared/guilty/ashamed we should feel about that. But again—the immune system is so damn complicated. A stopped clock is right twice a day, but if it also screams and tries to terrify you, it’s haunted and you should get rid of it.

At the same time, I think it’s worth entertaining the possibility that those of us who’ve had a round or two (or three or more) of covid may in some cases mount a less-than-ideal response to other pathogens. Again, not because this is entirely proven—we still don’t know either way—but it’s on the table as at least a partial explanation for the waves of surprisingly intense illness in the US this winter. So, a thought experiment: If we really are seeing a decreased or compromised immune response to pathogens after covid infections, what would it mean, for regular people?

Once I ease myself past my (honestly reasonable) initial feelings of avoidance, alarm, and dread), I think it would mostly mean two things:

It would be another reason to try not to get more covid than we have to, especially until we have a better handle on the long-term effects of the virus, and especially given that this thing is still mutating at a startling clip. Not just at the individual level, but communally.

It would be a reason to put more attention into both individual and especially communal measures to reduce exposure to other pathogens, including colds and flu. “Especially communal” because a lot of the people who want to avoid covid can’t, because of the way our society is structured, and those people are going to get slammed particularly hard with other viruses and secondary infections as well.

We know lots of things help with both of the above points: Ventilation and air filtration, high-quality masks on everyone who will wear them, staying home when symptomatic, keeping sick kids home, keeping up to date on all available vaccinations, avoiding indoor crowds during surges, handwashing, and disinfection (surfaces do matter for a lot of pathogens). And even the CDC (ok, NIOSH) agrees that getting enough sleep probably also helps. Doing as many of these things as our lives can accommodate will keep everyone healthier.

Ideally, our various levels of government would also provide material support for paid sick leave, testing, masks, and the rest of the list, but we live in this world, so I try to focus on the level of the community and the individual. Even if covid is hindering our immune responses to common pathogens, we can still help keep each other safer—and at the level of the individual life, safer can make all the difference.

Cobbling together your own personal covid forecast in 2023

Tl;dr: Case data is extra useless right now, look at hospitalizations and talk to your neighbors and friends.

Slightly more involved version: Case data is meaningless right now, both because of holiday reporting problems and because a tiny percentage of infections get captured as cases. (I wrote more on that toward the bottom of the email if you’re into it.)

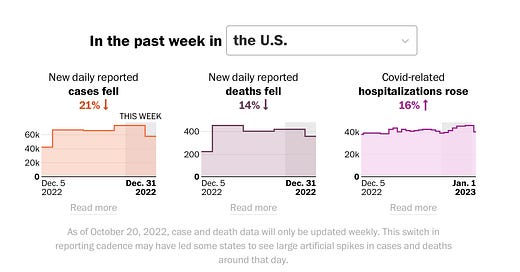

The Washington Post has a free-to-all page that lets you view hospitalizations in every US state (including DC, love you DC). At the top of that page, you can see that the holiday reporting effect I’ve written about for The Atlantic and at The Covid Tracking Project is still happening for the cases and death metrics. Hospitalization numbers, though, tend not to experience the holiday effect, so they’re the best metric many of us have now.

Nationally, US covid hospitalizations are just a little lower than they were back in the 2022 summer surge, but state numbers are much more important for decision-making than nationals. Scroll on down and pick your state and “hospitalizations” to see your state situation.

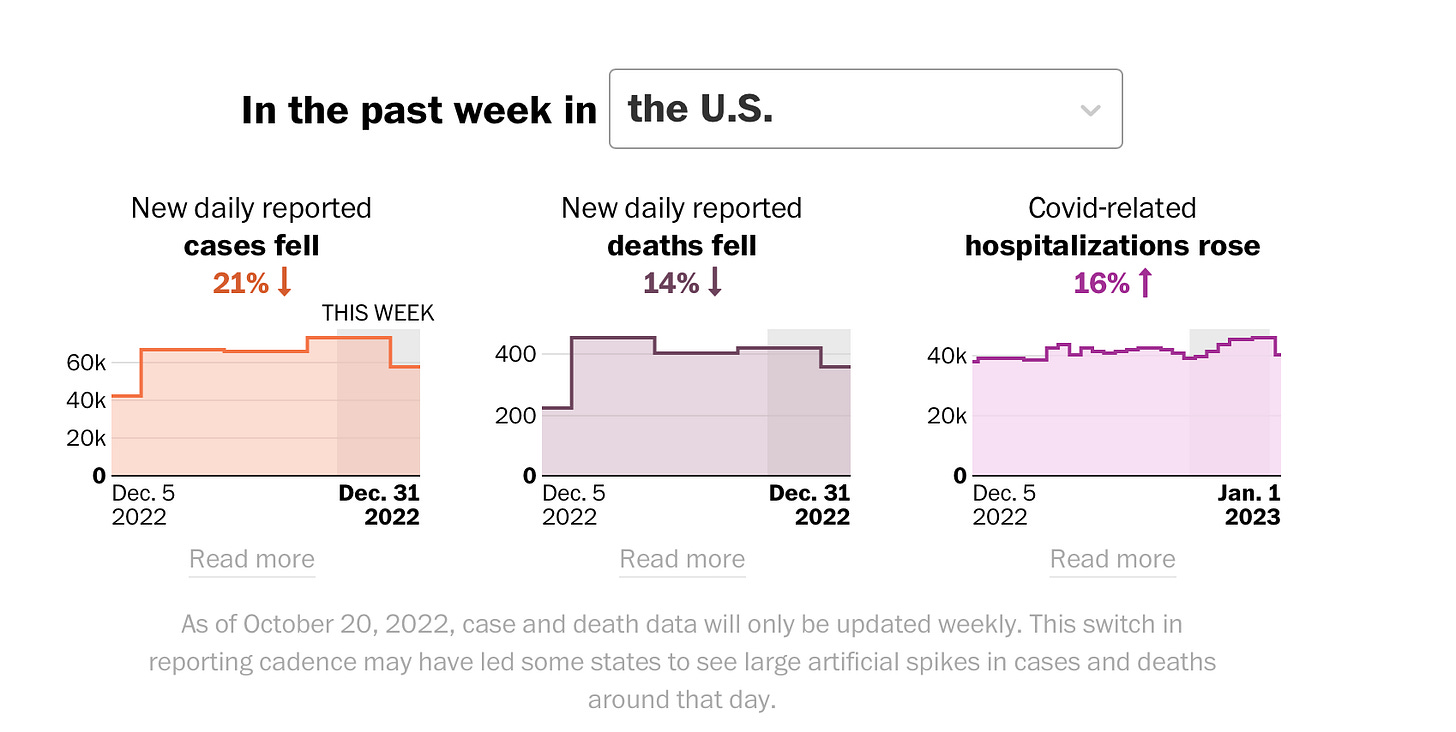

Here’s Oregon’s as of January 1, 2023:

Here’s how I’m using this data: Each individual covid infection is much, much less likely to be acutely dangerous now than in 2020 and 2021. Omicron infections were, on average, less severe, but there were just so many that a ton of people still got really sick, and many died. Now we seem to be in a different phase, given extremely widespread immunity from vaccines and infections, but hospitalizations are still rising and falling with surges in infections, so I’m still looking to hospitalizations as a proxy metric for actual community transmission.

This past summer, a ton of people I know in our area had covid—many for the first time, after years of being super careful. At that point, our state hospitalizations were elevated—not nearly as much as in the Delta wave that hit here in fall of 2021 or the Omicron wave of January 2022—but you can definitely see the midsummer bump in the chart above. Eyeballing the chart, Oregon is clearly back up at elevated numbers from right after Thanksgiving on, though we haven’t quite hit midsummer numbers yet. And I’m hearing more and more about covid infections locally, so that tracks.

(The New York Times’ covid tracker also offers county-level hospitalization data, which is a great thing to look at as well—you can search for your county on the main tracker page and then scroll down to see hospitalizations. This is useful especially for people who live in densely populated counties. If you live in a rural, low-population county, you’ll want to look at hospitalizations in nearby counties with major hospitals, because that’s often where the really sick patients are sent.)

Because we lack solid local numbers, we’re stuck with best guesses, but especially with the highly immune-evasive XBB swooping toward dominance, my best guess is that we’re gearing up for at least a modest late-winter surge in a lot of places across the US—though this won’t be reflected in case numbers, because most people don’t take an officially reported test (like a PCR test at a hospital or a rapid test at urgent care).

In really big surges previously, we’ve seen people start wearing masks and reducing social contact, especially after official death numbers started rising. I’ve seen a lot more people masking up recently than in previous months, but they’re still a small minority, and the CDC’s recommendation that people possibly kinda resume wearing masks indoors has been so quiet that I’d wager that most Americans don’t even know it happened. Or that cloth masks don’t substantially reduce Omicron transmission. And let’s talk about masks one more time, because honestly, modern high-filtration masks are amazing.

Good masks still work; two-way masking is much better than one-way

If you want to substantially reduce transmission, you need everyone to wear high-filtration masks—not cloth masks, not surgical masks. N95 and KN94/95s are both miles better than the simpler alternatives. (P100 is great if that’s a thing you can do, but most people are not going to accept the social and comfort downsides—especially kids.) But one-way masking just doesn’t cut it in the long term.

Back in the pre-Omicron days, a drastically simplified model from the CDC showed two unmasked people sharing air for 15 minutes was enough for infection. (Obviously 15 minutes isn’t magic, and lots of people got infected in much less—the 15 minutes thing was always lousy science communication, IMO.) One-way masking with an N95 bought the uninfected person 2.5 hours before getting covid. Two-way masking with N95s bumped it to 25 hours. The current Omicron variants are dramatically more transmissible than the ones around during early studies, so I wouldn’t expect those timings to still be accurate, but we can assume that two-way masking with high-filtration masks remains much more effective than one-way—and cloth masks are the SPF 4 Tanning Lotion of precautions—more trouble than they’re worth.

Our kid wears a KN94 or 95 to school, and with the exception of a couple of one-day fevers, she’s escaped the gnarly viruses that have run through our small town this fall and early winter. (We switched her from Airpops to size-small Powecoms from BonaFide because they’re more comfortable for her.) I know we’ll get popped one of these days, but I’m so grateful to have missed the waves we’ve missed.

Realistically, lots of careful and high-risk adults will have to spend a lot of time in one-way masking situations, not all kids will wear masks, and not all schools are socially accepting toward kids who do mask up. Which brings us back, again, to ventilation and filtration.

Ventilation and filtration sharply cut transmission

Fresh and filtered air saves lives and keeps everyone healthier. Here’s an extract from a roundup on the evidence from JAMA, emphasis mine:

…in a 2020 study that included 169 Georgia elementary schools, COVID-19 incidence was 39% lower in 87 schools that improved ventilation compared with 37 schools that did not (35% lower in 39 schools that improved ventilation through dilution alone [incidence rates, 2.94 vs 4.19 per 500 students enrolled] and 48% lower in 31 schools that improved ventilation through dilution combined with filtration [incidence rates, 2.22 vs 4.19 per 500 students enrolled]).1 A simulation model found that filtration with 2 high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) cleaners alone or combined with mask wearing could potentially reduce exposure to infectious particles by an estimated 65% or 90%, respectively.2

(Again, this study dealt with early, less-transmissible covid variants, so we should assume that Omicron’s friends and relations make those numbers worse, but the risk ratios are probably pretty steady.)

Many classrooms—and workplaces, and other spaces—that still don’t have good ventilation/filtration will accept and use donated air filters, especially if you keep up with refills. DIY Corsi-Rosenthal boxes still work. If you warn people in advance to dress warmly, lots of events can be made safer by cracking windows even in the winter. Everything helps, and not just with covid.

Why case counts are useless now (skip it if you’ve heard this one before)

Official case counts have never captured all covid infections, but in the US, they used to catch a good chunk of them, because the only way to get tested was to go someplace and have someone who was legally obligated to report the test stick a long swab up your nose. Now rapid at-home tests are the main way people here learn they have covid, and essentially zero of these tests ever get reported—plus, with flu and RSV and colds all circulating, it’s extremely likely that a huge number of people with covid never even take a rapid test—or they take one and call it a day, despite the fact that steady, repeated testing is the only real way to be reasonably sure that a given illness isn’t covid.

PLUS it’s the special time of year when the people who make the official data are on holiday breaks; at the Covid Tracking Project, we found that case counts tend to be artificially suppressed through the first week of January and then artificially inflated as they “catch up” in the week or two after. (Death data took longer to catch up.) So even if we normally had good case data, we wouldn’t right now.

At this point, case counts are so useless that I think looking at them does more harm than good. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

More joy in all seasons

For long-term health reasons, I’m a covid behavior outlier. If you’re reading this, you might be a bit of an outlier too. If so, this last bit is for you.

This holiday season, we attended extended-fam Thanksgiving for the first time since covid hit. Everyone took tests, one family stayed home with feverish kids, and someone else got sick mid-holiday but wore a mask and kept whatever it was from spreading. We brought a HEPA filter along. I’m really glad we went.

Indoor birthday and holiday parties also came back this year, and we masked up and attended a lot of things—and damned if the masks didn’t keep us healthy. Our daughter’s mini-school has been absolutely life-giving, and the community there has been super kind to us as we continued showing up with our faces covered long after most people stopped wearing masks. Every single classmate made it to our kid’s outdoor birthday party this year—her first since 2019—and it felt like a homecoming. We got to see visiting friends from all over, and every visit repaired things that had begun to feel frayed and thin.

On the extra-personal side, although I’ve had a few stretches of being too sick to work (or do anything else) because of chronic stuff, I didn’t get pneumonia or spend every night for six or eight months coughing my face off, like I did when we lived in a city and traveled a lot for work. Dumb luck + privilege + many years of making compromises and adapting our lives to extract maximal joy while accepting the realities of my imperfect immune system have let us find a good place as a family. I’m so grateful for the social contact we’ve been able to claw back. It was a good year as well as a hard one.

I hope 2023 brings you warmth and connection and an overflowing dose of real joy.

Love,

Erin